When is a disaster a DISASTER?

For practical purposes, it’s not a formal Disaster until someone says it is. Depending on who that person is, the resources you can draw on for recovery could differ dramatically. Only when local and state resources are overwhelmed can the Governor [and just the Governor] request federal assistance. Broadest support is available through Presidential Declared Disasters.

That’s when FEMA steps in and works directly with state agencies. The Resilience Action Guide explains how FEMA works, and more important, the roles urban foresters play in planning, mitigation, response, recovery and resilience.

Presidents declare National Disasters when state and local governments would be overwhelmed.

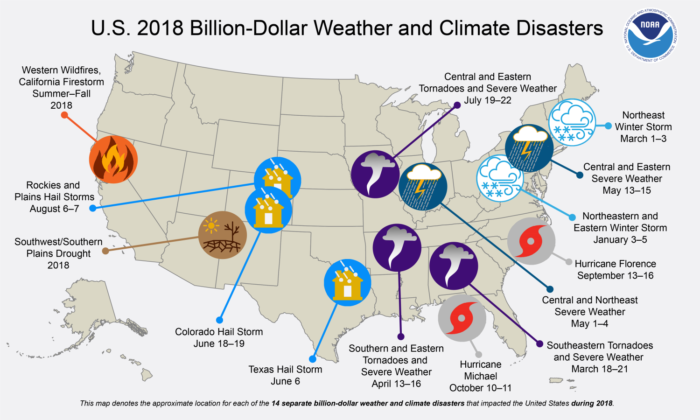

“Undeclared” disasters are devastating too! And frequent.

Don’t let nomenclature dictate planning, response or recovery. If you simply plan for the “big one” you may be unprepared for more frequent, less dramatic events. Add up as many as several hundred “minor” incidents a year in each state, and the costs can rival a mega-storm like Harvey.

Click here to see what sort of severe events your community experiences – hundreds of times annually.

Does a “hundred-year event” occur only once a century?

Not really. Major flooding events are commonly described to occur once every 10, 100, or 500 years. But that doesn’t mean if you’ve just suffered a “100-year” flood, you won’t see another one for a century. These projections are backward-looking and, more important, probalistic. Anyone who’s flipped a coin knows that [even though the odds of flipping heads is 50/50 each time you try] it’s certainly possible to throw heads three times in a row. Not likely, but possible.

Ellicott City, Maryland suffered three 100-year floods in a single decade. Officials and citizens still grapple with how to prevent future catastrophes, especially since major upstream development over past decades has disrupted the watershed.

Other storm events such as wind, ice, and fire also have frequency intervals. The likelihood of a catastrophic ice storm event at a specific location might be once every 30 years or more. But within the region that ice storms occur, a severe event will likely occur some place annually. Next year it could happen to your community. Again.

What about the trees?

Most trees fail during severe events because they’re diseased, or they’ve suffered pre-existing damage. As demonstrated in the Resilience Action Guide, comprehensive monitoring and maintenance before the fact will be your first line of defense when the storm hits.

Here’s a list of the most common tree defects, compiled by Professor Rich Hauer at the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point.