Context

Portland has one of the most unevenly distributed tree canopy coverage of any American city: from one neighborhood to the next, the variation in canopy can range from as low as 5%, to as high as 70%. Predictably, as with most cities, this discrepancy falls clearly along class and racial lines. In a recent study conducted by Portland State University, neighborhoods with households with the highest incomes have on average 20% more canopy than those in the lowest income neighborhoods.

The vast majority of Portland’s population lives on the east side of the Willamette River, where the average tree canopy cover hovers around 21%. This area is also home to almost all of Portland’s communities of color, meaning that the services and benefits of the urban forest are a luxury that most Portland residents have not been able to afford.

Plan for Equity

City officials have cited several reasons for this inequity, including the process and timing of annexation of neighborhoods, lack of public investment, and development. With admirable candor, the city has also admitted that many existing inequities were created, enabled, and maintained by its own public policy. In 2017, to start addressing these gaps, Portland Parks & Recreation created their Five-year Racial Equity Plan, with the main objective to provide equitable city services to all residents and increase access to trees and urban forest services for communities of color, including low-income, refugee, and immigrant communities. Coupled with an expansion in their funding for tree planting, city officials set out to determine how to plant for the “most public benefit”. Surveys were developed, translated into several languages, and deployed; a Community Advisory Committee was formed; and already-established community groups were approached. What they learned will not only add more tree coverage to the map, but will also transform how the city government and their residents view one another and communicate.

City officials found fundamentally legitimate, significant barriers that low-income, immigrant, and communities of color face that prevent them from planting and caring for trees. Varying cultural values and relationships with trees, competing priorities and limited resources, cost, disempowerment of renters, fears of gentrification, and a historic lack of authentic engagement from the city were just a few.

“Growing the urban forest equitably first requires a better understanding of the concerns and needs of communities around trees and planting. A new tree must be watered for several years, pruned when young to develop good structure, and cared for over its long lifespan. Generally, these costs are all absorbed by property owners,” says Angie DiSalvo, a manager at Portland’s Urban Forestry Division – costs that most low-income renters and property owners could not bear. Additionally, renters discussed fears of eviction if asking or advocating for more trees.

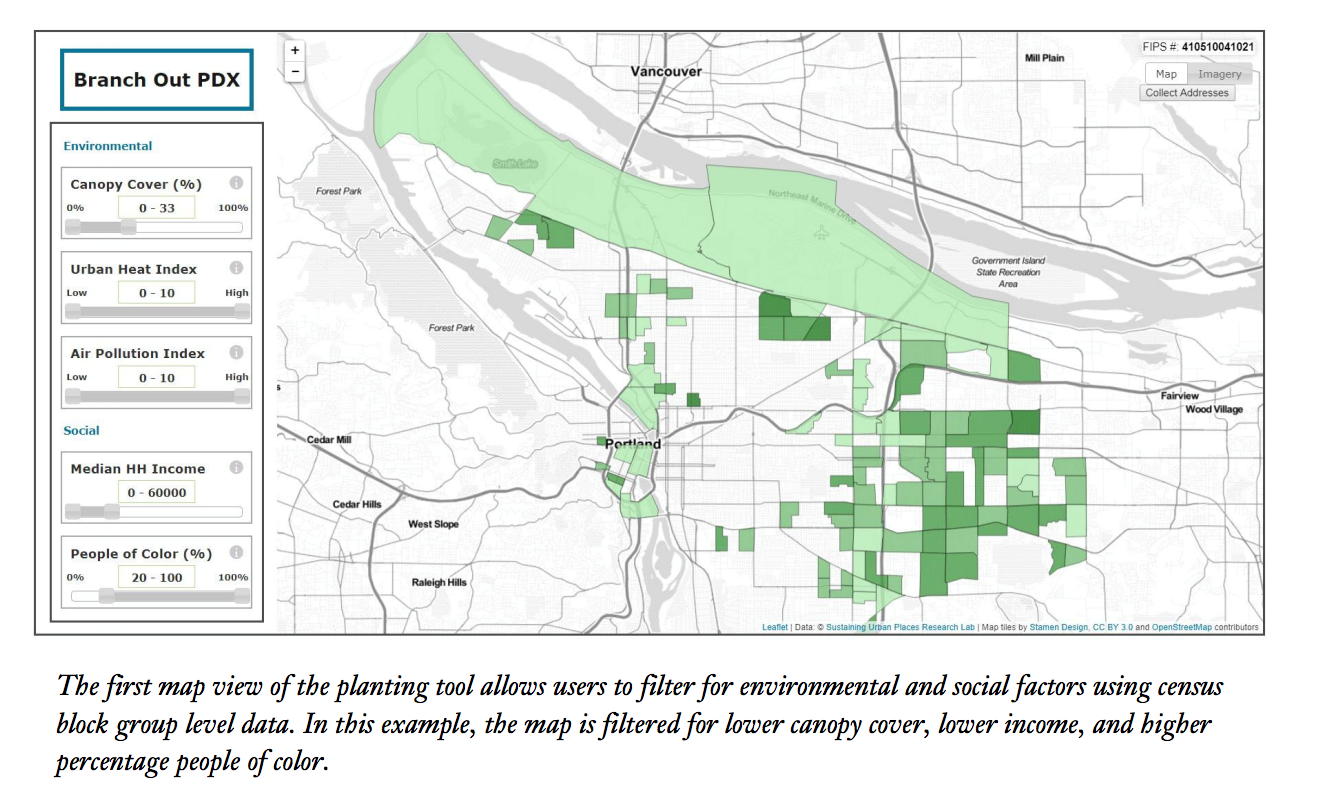

In addition to community engagement, new data-driven tech tools were developed to help identify specific areas of the city where tree planting could have biggest impact. Portland State University developed an online planting tool, “Branch Out PDX”, that uses social and environmental factors to prioritize and identify planting opportunities, by both census block group and individual tax lot.

Building Trust is Key

Tree planting outreach to underserved communities must include culturally-specific elements, such as conducting culturally-specific educational events, tailoring events to the community, providing translation and interpretation services, and adapting existing volunteer programs to specific communities. Examples like advertising on Russian radio and Spanish-language newspapers helped community engagement liaisons reach members of diverse ethnic and immigrant groups.

Many communities of color, immigrants, and refugees expressed having a personal or historic lack of trust with government agencies and nonprofits, either in their country of birth or in the United States. Without trust or relationships with the entities who were planting trees, participants said they were not likely to participate. Common outreach methods, particularly door-to-door canvassing, were not only less effective than learning about opportunities through an already trusted source, but perceived as suspicious. Participants expressed that hiring their community members would not only improve their economic situation, but would build relationships, increase trust, and cultivate leaders from their communities that could champion efforts like tree planting.

Interestingly, a lack of understanding around the symbolism of trees and how they are perceived by different cultures was identified as a common thread in government-resident relations. City officials learned that value is relative, and that the constantly asserted ecosystem services pitch doesn’t resonate with everyone. “A mismatch exists between professional framing of the importance of trees and community interests,” explains DiSalvo. “A one‐size‐fits‐all tree planting mentality will not work to meet the needs of various communities.” For example, when asked what benefits trees provide, participants commonly cited food, medicine, wood, and shade. Many of the most common benefits that municipalities often promote – like carbon sequestration and stormwater management – didn’t even make the list.

Survey results repeatedly expound that tactic of using multiple approaches to build community‐specific value for trees. Many residents stated that merely recognizing the placement of trees at the center of communal public spaces, where relationships are built and fostered, was a great way to start building on this value.

Lessons Learned

“Building relationships with historically underserved communities takes time, requires actively

listening to the desires and needs of those who have been left out of conversations in the past, and

should be a continuous effort – meaning, not just project-based,” concludes DiSalvo. One strategy currently being employed is making Portland’s Urban Forestry Commission more representative by bringing on members from east Portland.

Portland is still in the beginning stages of implementing their equity plan, and they have a long way to go in developing robust relationships with community partner organizations as well as devising new funding sources and mechanisms to support the work. But ingrained in the process is a new recognition of the role the city plays in engaging those who have not historically been a part of tree planting campaigns. By addressing key issues – maintenance responsibility, language barriers, and the structure of government – and learning from past mistakes, the city can transform a previously reluctant set of neighborhoods into drivers, or even planters, of change.

Funding

- City of Portland Parks & Recreation

Implementation

- Identify and reconcile community-specific values that can inform tree planting and care

- Increase representation from East Portland neighborhoods on the City’s Urban Forestry Commission

- Equip neighborhoods that receive new trees with financial, technical, and physical supports necessary for maintenance